2020.2 Vitis™ - Runtime and System Optimization - Acceleration BasicsSee Vitis™ Development Environment on xilinx.com |

Acceleration Concepts¶

Rather than diving immediately into the API, especially if you don’t have much experience with acceleration, let’s start with a simplified analogy to help explain what must happen in an acceleration system.

Imagine that you have been given the job of giving tours of your city. Your city may be large or small, dense or sparse, and may have specific traffic rules that you must follow. This is your application space. Along the way, you are tasked with teaching your wards a specific set of facts about your city, and you must hit a particular set of sights (and shops - you have to get paid, after all). This set of things you must do is your algorithm.

Given your application space and your algorithm, you started small: your tours fit into one car, and every year you would buy a new one that was a bit bigger, a bit faster, and so on. But, as your popularity grew, more and more people started to sign up for the tours. There’s a limit to how fast your car can go (even the sports model), so how can you scale? This is the problem with CPU acceleration.

The answer is a tour bus! It might have a lower top speed and take much longer to load and unload than your earlier sports car idea, but you can transport many more people - much more data- through your algorithm. Over time, your fleet of buses can expand and you can get more and more people through the tour. This is the model for GPU acceleration. It scales very well - until, that is, your fuel bills start to add up, there’s a traffic jam in front of the fountain, and wouldn’t you know it, the World Cup is coming to town!

If only the city would allow you to build a monorail. On their dollar, with the permits pre-approved. Train after train, each one full, making all the stops along the way (and with full flexibility to bulldoze and change the route as needed). For the tour guide in our increasingly tortured metaphor, this is fantasy. But for you, this is the model for Vitis acceleration. FPGAs and ACAPs combine the parallelism of a GPU with the low-latency streaming of a domain-specific architecture for unparalleled performance.

But, as the joke goes, even a Ferrari isn’t fast enough if you never learn to change gears. So, let’s abandon metaphor and roll up our sleeves.

Identifying Acceleration¶

In general, for acceleration systems we are trying to hit a particular performance target, whether that target is expressed in terms of overall end-to-end latency, frames per second, raw throughput, or something else.

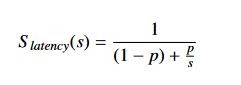

Generally speaking, candidates for acceleration are algorithmic processing blocks that work on large chunks of data in deterministic ways. In 1967, Gene Amdahl famously proposed what has since become known as Amdahl’s Law. It expresses the potential speedup in a system:

In this equation, S_latency represents the theoretical speedup of a task, s is the speedup of the portion

of the algorithm that benefits from acceleration, and p represents the proportion of the execution time the

task occupied pre-acceleration.

Amdahl’s Law demonstrates a clear limit to the benefit of acceleration in a given application, as the portion of the task that cannot be accelerated (generally involving decision making, I/O, or other system overhead tasks) will always become the system bottleneck.

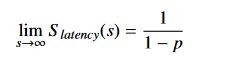

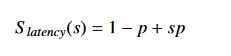

If Amdahl’s Law is correct, however, then why do so many modern systems use either general-purpose or

domain-specific acceleration? The crux lies here: modern systems are processing an ever-increasing amount of

data, and Amdahl’s Law only applies to cases where the problem size is fixed. That is to say, the limit is

imposed only so long as p is a constant fraction of overall execution time. In 1988 John Gustafson and Edwin

Barsis proposed a reformulation that has since become known as Gustafson’s Law. It re-casts the problem:

Again, S_latency represents the theoretical speedup of a task, s is the speedup in latency of the task

benefiting from parallelism, and p is the percentage of the overall task latency of the part benefiting from

improvement (prior to the application of the improvement).

Gustafson’s Law re-frames the question raised by Amdahl’s Law. Rather than more compute resources speeding up the execution of a single task, more compute resources allow more computation in the same amount of time.

Both of the laws frame the same thing in different ways: to accelerate an application, we are going to parallelize it. Through parallelization we are attempting to either process more data in the same amount of time, or the same amount of data in less time. Both approaches have mathematical limitations, but both also benefit from more resources (although to different degrees).

In general, FPGAs and ACAPs are useful for accelerating algorithms with lots of “number crunching” on large data sets - things like video transcoding, financial analysis, genomics, machine learning, and other applications with large blocks of data that can be processed in parallel. It’s important to approach acceleration with a firm understanding of how and when to apply external acceleration to a software algorithm. Throwing random code onto any accelerator, FPGA or otherwise, does not generally give you optimal results. This is for two reasons: first and foremost, leveraging acceleration sometimes requires restructuring a sequential algorithm to increase its parallelism. Second, while the FPGA architecture allows you to quickly process parallel data, transferring data over PCIe and between DDR memories has an inherent additive latency. You can think of this as a kind of “acceleration tax” that you must pay to share data with any heterogeneous accelerator.

With that in mind, we want to look for areas of code that satisfy several conditions. They should:

Process large blocks of data in deterministic ways.

Have well-defined data dependencies, preferably sequential or stream-based processing. Random-access should be avoided unless it can be bounded.

Take long enough to process that the overhead of transferring the data between the CPU and the accelerator does not dominate the accelerator run time.

Alveo Overview¶

Before diving into the software, let us familiarize ourselves with the capabilities of the Alveo Data Center accelerator card itself. Each Alveo card combines three essential things: a powerful FPGA or ACAP for acceleration, high-bandwidth DDR4 memory banks, and connectivity to a host server via a high-bandwidth PCIe link. This link is capable of transferring approximately 16 GiB of data per second between the Alveo card and the host at Gen3x16, and higher rates for newer generations.

Recall that unlike a CPU, GPU, or ASIC, an FPGA is effectively a blank slate. You have a pool of very low-level logic resources like flip-flops, gates, and SRAM, but very little fixed functionality. Every interface the device has, including the PCIe and external memory links, is implemented using at least some of those resources.

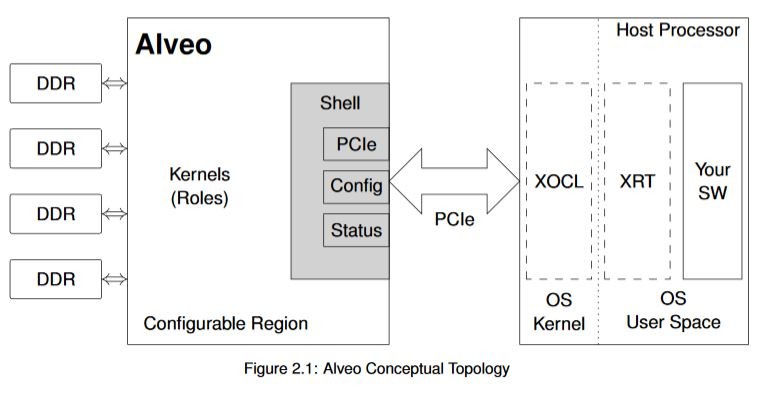

To ensure that the PCIe link, system monitoring, and board health interfaces are always available to the host processor, Alveo designs are split into a shell and role conceptual model. The shell contains all of the static functionality: external links, configuration, clocking, etc. Your design fills the role portion of the model with custom logic implementing your specific algorithm(s). You can see this topology reflected here:

The Alveo FPGA is further subdivided into multiple super logic regions (SLRs), which aid in the architecture of very high-performance designs. But this is a slightly more advanced topic that will remain largely unnoticed as you take your first steps into Alveo development.

Alveo cards have multiple on-card DDR4 memories. These memories have a high bandwidth to and from the Alveo device, and in the context of OpenCL are collectively referred to as the device global memory. Each memory bank has a capacity of 16 GiB and operates at 2400 MHzDDR. This memory has a very high bandwidth, and your kernels can easily saturate it if desired. There is, however, a latency hit for either reading from or writing to this memory, especially if the addresses accessed are not contiguous or we are reading/writing short data beats.

The PCIe lane, on the other hand, has a decently high bandwidth but not nearly as high as the DDR memory on the Alveo card itself. In addition, the latency hit involved with transferring data over PCIe is quite high. As a general rule of thumb, transfer data over PCIe as infrequently as possible. For continuous data processing, try designing your system so that your data is transferring while the kernels are processing something else. For instance, while waiting for Alveo to process one frame of video you can be simultaneously transferring the next frame to the global memory from the CPU.

There are many more details we could cover on the FPGA architecture, the Alveo cards themselves, etc. But for introductory purposes, we have enough details to proceed. From the perspective of designing an acceleration architecture, the important points to remember are:

Moving data across PCIe is expensive - even at the latest generation, latency is high. For larger data transfers, bandwidth can easily become a system bottleneck.

Bandwidth and latency between the DDR4 and the FPGA is significantly better than over PCIe, but touching external memory is still expensive in terms of overall system performance.

Within the FPGA fabric, streaming from one operation to the next is effectively free (this is our train analogy from earlier; we’ll explore it in more detail later).

Xilinx Runtime (XRT) and APIs¶

Although this may seem obvious, any hardware acceleration system can be broadly discussed in two parts: the hardware architecture and implementation, and the software that interacts with that hardware. For Vitis, regardless of any higher-level software frameworks you may be using in your application such as FFmpeg, GStreamer, or others, the software library that fundamentally interacts with the Alveo hardware is the Xilinx Runtime (XRT).

While XRT consists of many components, its primary role can be boiled down to three simple things:

Programming the FPGA/ACAP kernels and managing the life cycle of the hardware

Allocating memory and migrating that memory between the host CPU and the card

Managing the operation of the hardware: sequencing execution of kernels, setting kernel arguments, etc.

These three things are also, in the same order, the most to least “expensive” operations you can perform on an FPGA. Let’s examine that in more detail.

Programming the kernels into the hardware inherently takes some amount of time. Depending on the capacity of the FPGA, the PCIe bandwidth available to transfer the configuration image, etc., the time required is typically in the order of dozens to hundreds of milliseconds. This is generally a “one time deal” when you launch your application, so the configuration hit can be absorbed into general setup latency, but it’s important to be aware of. There are applications where Alveo is reprogrammed multiple times during operation to provide different large kernels. If you’re planning to build such an architecture, incorporate this configuration time into your application as seamlessly as possible. It’s also important to note that while many applications can simultaneously use the hardware, only one image can be programmed at any point in time.

Allocating memory and moving it around is the real “meat” of XRT. Allocating and managing memory effectively is a critical skill for developing acceleration architectures. If you don’t manage memory and memory migration efficiently, you will significantly impact your overall application performance - and not in the way you’d hope! Fortunately XRT provides many functions to interact with memory, and we will explore those specifics later on.

Finally, XRT manages the operation of the hardware by setting kernel arguments and managing the kernel execution flow. Kernels can run sequentially or in parallel, from one process or many, and in blocking or non-blocking ways. The exact way your software interacts with your kernels is under your control, and we will investigate some examples of this later on.

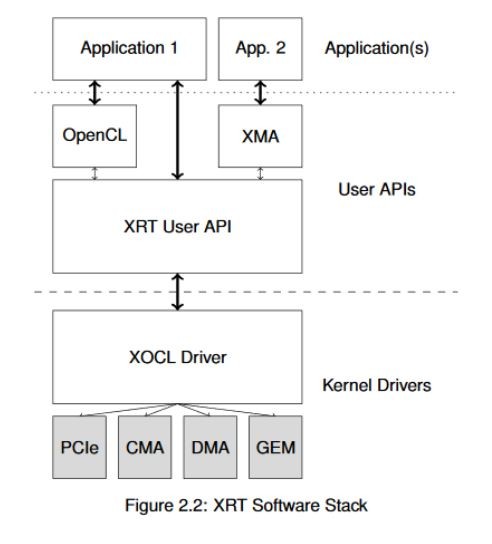

It’s worth noting that XRT is a low-level API. For very advanced or unusual use models you may wish to interact with it directly, but most designers choose to use a higher-level API such as OpenCL, the Xilinx Media Accelerator (XMA) framework, or others. The following figure shows a top-level view of the available APIs. For this document, we will focus primarily on the OpenCL API to make this introduction more approachable. If you’ve used OpenCL before you will find it mostly similar (although Xilinx does provide some extensions for FPGA-specific tasks.)

In the next section, you’ll learn the basic concepts of memory management you’ll need to understand to optimize your application.

Copyright© 2019-2021 Xilinx