Architecture¶

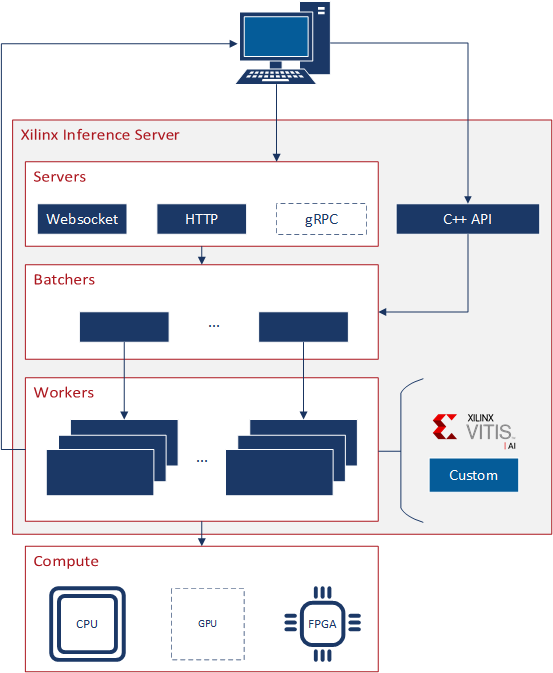

Fig. 1 Server architecture overview¶

Overview¶

Fig. 1 shows a high-level view of the Server’s architecture. At the top, we have a client who can make a request to the Server using HTTP/REST, WebSocket, gRPC or the C++ API [1]. This request must be made to a particular worker that must be active in the Server. Each received request is passed to a batcher associated with the targeted worker independent of its origin. The batcher will combine individual requests into a batch and pass it to the worker for execution. The worker parses the batch, processes each request contained within, and responds to the client. Internally, the worker can leverage any C++ logic and/or use external libraries such as Vitis AI or machine learning frameworks to process the request. This flexibility enables the Server to take advantage of any hardware accelerator with the appropriate worker. The response to the client is made using the same API as the original request.

Ingestion¶

There are a number of ways to get data into the system for inference.

In general, each protocol has a custom interface to the client and requires explicit handling in the Server to accept this initial request.

After receiving the client’s request in the Server, each supported protocols’ handler converts the incoming data into an InferenceRequest object.

This object, plus some metadata, is packed into a RequestContainer object and passed to the appropriate batcher.

API¶

The APIs used for this project are based on ‘KServe’s v2 specification’ where possible. The API defines endpoints in different categories: health, metrics and prediction. The health APIs define endpoints to get Server metadata and check server readiness. The metrics API defines a single endpoint for exposing the collected metrics using the Prometheus format. The prediction APIs are used to make inferences.

For inference, we provide load and unload endpoints for clients to control which workers are active (and how many instances of each).

The load API accepts an optional set of parameters that define load-time parameters.

On success, the load API returns a string corresponding to the endpoint that clients should use to make prediction requests from the loaded worker.

Note, this usage differs slightly from KServe’s specifications.

With KServe, the load API returns only the status code and the requests are made to the same endpoint as the string specified in the load request.

It also doesn’t have the notion of load-time parameters.

In our case, there are parameters we need to pass at load-time, which results in potentially different endpoints if multiple workers with different configurations are loaded at once.

To maintain compatibility, we do guarantee that the first worker loaded for a particular model, independent of configuration, will be at the same endpoint as the load request.

Therefore, a KServe client is free to ignore the contents of the response and make requests to the endpoint without resulting in errors.

There’s also a modelLoad API which behaves more similarly to how KServe expects and is intended for use with using the server with a model repository.

We currently do not support the optional version information associated with a model defined in the KServe specification. After a particular worker is loaded, inference requests can be made to it by constructing the appropriate request object and sending it to the prediction endpoint. The format of the request object in HTTP matches KServe’s specification while an equivalent C++ object is used for the C++ API.

HTTP/REST and WebSocket¶

The HTTP/REST and WebSocket functionality in the Server is provided using Drogon. We chose to use Drogon for our web framework for a few reasons:

Based on the benchmarks at ‘<TechEmpower’, Drogon is high-performing (unlike CppCMS and Treefrog)

It is more stable and active than Lithium, another high-performing framework (Lithium is newer)

Active on Github with versioned releases (unlike Pistache and Lithium)

The various endpoints from the API are registered in the Drogon’s HTTP controller along with their request handler functions.

Drogon uses a configurable number of threads to run these request handlers.

When a REST request is made to an endpoint, the request data and callback function are provided for the handler to process the request and then respond to the client.

To avoid blocking the finite number of handler threads with potentially long-running inference requests, we use an asynchronous architecture in the handler.

The received request is packed into a RequestContainer object and pushed into a thread-safe lock-free multi producer/consumer queue to go to the target worker’s batcher.

The HTTP server code is in src/amdinfer/servers/http_server.*.

Drogon also provides a WebSocket server, which is currently used experimentally to run predictions on videos from certain workers.

The WebSocket API is custom.

At this time, the client provides a URL to a video that the worker will retrieve and analyze frame-by-frame and send back to the client but this is subject to change.

The WebSocket server code is in src/amdinfer/servers/websocket_server.*.

gRPC¶

The gRPC functionality is provided through a custom implementation of a gRPC server.

There are some examples in the gRPC repository on Github that can be used for reference.

It makes new dynamic objects to keep track of the incoming requests and a state machine is embedded inside to track state.

A pointer to this object, CallData, is put into the callback for the request so when the worker finishes this request, it will use it to respond to the request.

After the response, the state machine is marked to finish and the object deallocates itself.

The gRPC server code is in src/amdinfer/servers/grpc_server.*.

C++ API¶

The C++ API allows users to compile custom applications that link directly to the Server’s backend. As a result, using the C++ API will yield the highest performance of any ingestion method.

The C++ API provides functions similar to the prediction API used in HTTP.

The API lets users load workers and make inference requests.

The inference request is packed into a RequestContainer object and pushed to the target worker’s batcher.

An std::promise is returned to the user to retrieve the result.

The public API is defined in include/amdinfer/clients/native.hpp and the implementation is in src/amdinfer/clients/native.cpp.

Batching¶

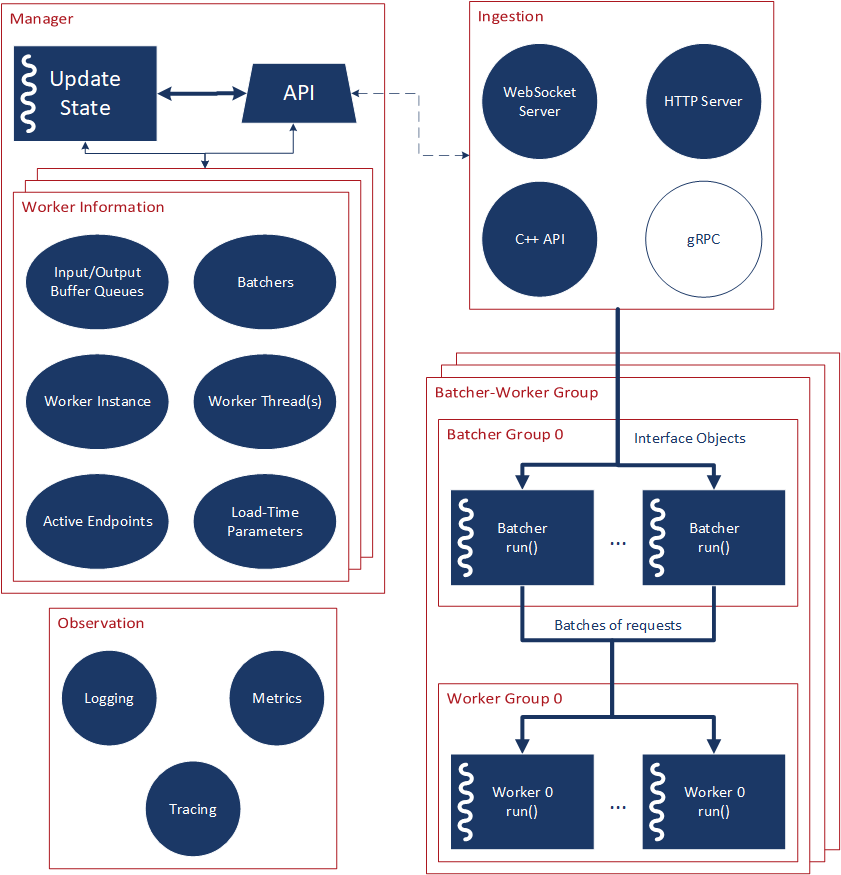

Fig. 2 More detailed look at the Server architecture¶

Batching is a technique used in hardware to improve throughput performance.

Batching groups multiple smaller requests from the user into one large request to improve the performance of hardware accelerators.

However, user requests at the software application level are usually not conveniently available as complete batches as they come one at a time.

The Server incorporates batching as a transparent step in the pipeline that groups all incoming requests, independent of the source of the original request from the client (see Fig. 2).

The implementations of the batchers are in src/amdinfer/batching.

The base batcher class defines a common interface for all batcher implementations and has some basic common properties.

Each batcher has two thread-safe queues (one for input and one for output), a configured batch size and a string identifying the worker group it’s attached to.

The batcher runs as a separate thread that monitors its input queue to process incoming RequestContainer objects from all ingestion methods and pushes completed Batch objects on the output queue.

Each batcher implementation defines a run() method that provides the logic with which the batcher produces a batch.

A worker (and by extension, the worker group) specifies which batcher implementation should be used to prepare batches for it (as well as the batch size) and each worker group shares a set of batchers.

This configuration is determined at compile-time and built into the definition of the worker.

A Batch is made up of three basic components: InferenceRequest objects and input/output buffers.

InferenceRequest objects are direct C++ implementations of the information present in the KServe API of an inference request structured in a similar format.

They provide an ingestion-agnostic data format that all workers can process.

The batcher is responsible for getting memory from the memory pool that is sized appropriately to contain the incoming batch size of data as a buffer.

The worker provides a list of allocators that the batcher is allowed to use when requesting memory.

Most commonly, each buffer can be used to represent one batch-size worth of contiguous memory but its exact nature depends on the buffer implementation that the worker has requested.

In this case, the batcher’s job is to take individual requests and move its data into one slot of this buffer and construct the corresponding InferenceRequest object.

Batchers have some flexibility with how these batches are constructed, which is why multiple batcher implementations are possible and supported in the AMD Inference Server.

For example, one batcher may allow partial batches to be pushed on after enough time whereas this may not be allowed by another batcher.

Assuming that contiguous batches are expected, the batcher should request memory from the pool on the first request of a new batch. As new requests come in, their data is copied over to the newly allocated memory so it’s contiguous for downstream processing. The memory that was used initially by the ingestion layer can now be freed.

Workers¶

Workers perform the computation. They are the smallest unit that the Server manages. A worker may be as simple or complex as you like: as long as it adheres to the interface. Each worker is compiled as a shared object that the Server can dynamically open at load-time. Thus, new workers can be loaded and unloaded without stopping the server.

Workers are defined in src/amdinfer/workers.

The CMakeLists.txt file builds each worker as libworkerX.so where X corresponds to the name of the C++ file defining the worker in PascalCase.

Organization and Lifecycle¶

The base Worker class provides the template of all workers for the Server. This class defines the lifecycle methods of the worker that are called by the Server. This lifecycle is defined as follows:

init(): perform low-cost initialization of the workeracquire(): acquire any hardware accelerators/resources and/or perform any high-cost initialization for the workerrun(): the main body of the worker performs the chosen computations on incoming batchesrelease(): release any hardware accelerators/resourcesdestroy(): perform any final operations prior to shutdown

The first two steps set up the worker while the latter two tear it down and are performed in this order by the Server.

The body of these methods must be provided by each worker implementation in the corresponding doX() methods (e.g. doInit()).

At load-time, the server will create an instance of the worker using its getWorker() method:

extern "C" {

amdinfer::workers::Worker* getWorker() { return new amdinfer::workers::MyWorkerClass(); }

}

This instance is saved internally and the first two methods above are called to initialize the worker.

The worker’s batcher is also started by the server at this time.

Finally, the worker’s run() method is started as a separate thread with the batcher’s output queue passed as the input queue to the worker.

This method performs the body of the work.

In an infinite loop, this method should wait for incoming batches from the worker’s input queue, process the requests, and respond to the clients.

To unload a worker, the State sends a nullptr to the worker, which should terminate the run() thread.

This thread is joined and the last two lifecycle methods are called to safely clean up the worker.

Workers must also define a getAllocators() method to choose which allocators can be used by the batcher when it’s preparing the incoming batch.

std::vector<MemoryAllocators> MyWorkerClass::getAllocators() const {

return {MemoryAllocators::Cpu};

}

Improving Performance¶

Having multiple workers of the same kind can improve performance if there are many incoming batches.

Multiple identical workers are grouped into one worker group (see Fig. 2).

Each worker group shares one batcher group i.e. each batcher in a batcher group pushes its batches to a common queue that each worker in a worker group is dequeuing from.

This structure enables any worker in the group to pull a new batch when it can process it.

Therefore, each worker should only pull from this common queue when it can actually process the data.

To load a new worker into an existing group, the worker should be loaded with the load-time parameter share set to false.

External Processing¶

Workers, by virtue of their generic structure, may be highly complex and call entirely external applications for processing data. The AMD Inference Server supports this use case and suggests the following for organizing code:

The external application can be brought in similarly to how existing external applications are brought in already with CMake

The general worker structure should follow the existing model for native workers as defined above

After determining that a request is valid, the worker should convert the native request into something that the external application understands

Then, the data can be passed over to the external application.

The external application should return its results back to the worker

The response needs to be converted back to the native format to reply to the client

Currently, there are no rules that the Server enforces for what workers are allowed to do and if they must expose any other functionality to the Server though this will change in the future. For example, the Server will eventually need to send health check requests to workers that must be responded to appropriately.

XModel¶

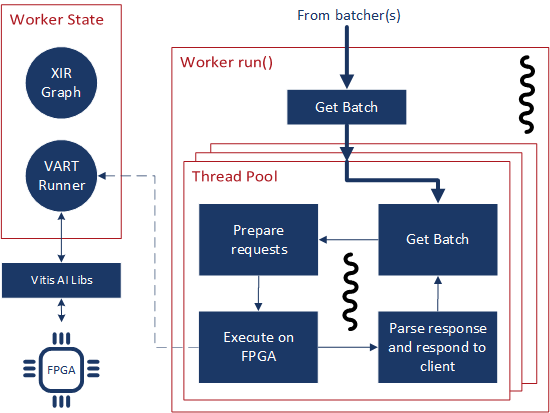

Fig. 3 The XModel worker¶

As perhaps the most complex worker thus far, the architecture of the XModel worker is examined here in greater detail.

The XModel worker is intended to run an arbitrary XModel specified by the user on a Xilinx FPGA [2].

We take a look at the lifecycle of this worker in the following sections.

The XModel worker is using the VartTensor allocator.

std::vector<MemoryAllocators> Xmodel::getAllocators() const {

return {MemoryAllocators::VartTensor};

}

Initialization¶

The XModel worker needs a path to an XModel to run at load-time. This XModel file is opened and parsed to get the graph and the first DPU subgraph (i.e. the first subgraph in the graph that is supposed to run on the FPGA). In the future, we may support running an arbitrary number of subgraphs but this simple case is often sufficient. Using this subgraph, we create a Runner, which is a thread-safe object defined in the Vitis-AI runtime and is responsible for submitting requests to the FPGA. These objects are all saved as part of the internal state of the worker.

Acquisition¶

Since the Runner is thread-safe, we can use multiple threads to push data to the FPGA from the same Runner to improve throughput. To enable this functionality, we incorporate an internal thread pool in the XModel worker. Here, we set the size of this thread pool based on user parameters.

Run¶

As with all workers, the XModel worker pulls batches from its inputs queue and checks if it’s a nullptr before continuing to process the batch.

If valid, the batch is pushed into the thread pool, which internally assigns a lambda function to one of its internal threads to perform the processing.

This lambda function performs the same work that other workers normally perform directly in the run() method itself.

Here, for each batch, we push the data to the FPGA with the Runner and start preparing the response while waiting for the asynchronous operation to return.

Then, the response from the FPGA is parsed, the client response is populated with this data and the callback is called to respond back to the client.

To prevent the worker from pulling too many batches, an atomic counter is used to track the number of outstanding batches in the worker. If the number is above a configured amount, then the worker doesn’t pull more batches until it has processed some of the ones it already has. This throttling is necessary for the work-stealing model for workers to work.

Cleanup¶

There is almost no special cleanup required as the Vitis-AI objects that are part of the worker’s state are smart pointers and are cleaned by the worker’s destructor. THe only non-default implementation of the clean-up functions is to stop the internal thread pool and join the threads.

Observation¶

Visibility into the server and its operations is provided through logging, metrics and tracing.

The implementations of these components is in src/amdinfer/observation.

Logging¶

The Server uses spdlog to provide logging.

By default, one logger is configured with initLogging(), which logs data to a file on the disk and prints warning messages to the terminal as well.

The preprocesser directive form of logging is used throughout the Server, which enables all logging data to be optionally removed at compile-time.

Look at Logs for more information.

Metrics¶

The Server uses prometheus-cpp to provide metric collection in the Prometheus format.

The metric data can be queried via the web server at the /metrics endpoint.

At compile-time, the metrics of interest must be defined in the Metrics class.

It provides methods for functions in other classes to modify the metric state.

Metric collection can be disabled at compile-time with a CMake option.

Look at Metrics for more information.

Tracing¶

The Server uses opentelemetry-cpp to provide tracing. Tracing tracks the time taken for different sections of the architecture to process a single request. This data can be visualized in the Jaeger UI or Grafana. Tracing data can be disabled at compile-time with a CMake option.

Look at Tracing for more information.